What is Executive Function?

By Allie Bradford Brown

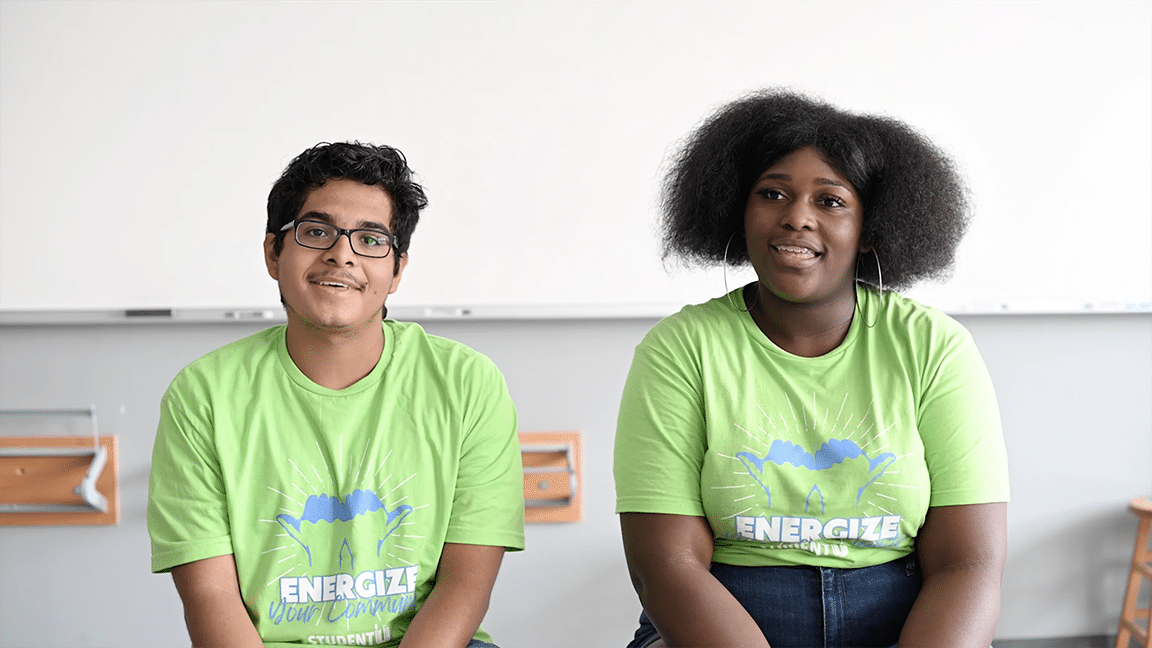

Welcome to the Youth Work 101 Series! Student U offers this blog series to support youth work practitioners, educators, advocates for young people, and after-school professionals in their work by sharing what has worked for us. For insights on this month’s topic, Allie Bradford Brown, Student U’s Advancement Writing Associate, interviewed Alex Lowe Turner, Student U’s Director of Academic Support.

*Disclaimer: Alex is not a neuropsychologist or an expert in brain development. Her expertise comes from her BS in Elementary Education, M.Ed. in Special Education, and decade-long professional tenure at Student U.*

What is Executive Function?

Although the definition of Executive Function has varied over the years, the consensus among educators and experts in human development is that these skills matter.

Executive Function is an umbrella term for the complex, cognitive skills and processes that help people reach an end goal. Executive functioning includes the “soft skills” that affect our ability to think flexibly, analyze situations, and manipulate complex pieces of information. Examples of executive function skills include

- Self-monitoring and self-regulation: the ability to check in with yourself and see how you’re doing with a task both emotionally and logistically; to choose from alternatives and control impulses

- Organization: the ability to arrange, plan, and manage your tasks

- Thinking flexibly: the ability to respond to changes in plans or expectations with new ideas for moving forward

- Backwards planning: the ability to visualize an end goal then plan the what you need to accomplish to achieve that goal

Can executive function be taught?

There is so much to learn in school besides the content skills we typically think of (like math, science, reading, or history), and executive function skills are essential. Unfortunately, as parents and educators, we may erroneously assume that students will pick up executive function skills in the process of learning the content without direct instruction. This is why a math whiz can fail a math class, or a high-functioning student can earn an “A” in math without understanding any of it.

There is so much to learn in school besides the content skills we typically think of (like math, science, reading, or history), and executive function skills are essential. Unfortunately, as parents and educators, we may erroneously assume that students will pick up executive function skills in the process of learning the content without direct instruction. This is why a math whiz can fail a math class, or a high-functioning student can earn an “A” in math without understanding any of it.

Poor grades are often a sign of executive function challenges rather than lack of intelligence or ability to learn–think of that math whiz who fails math because his homework is always in the bottom of his backpack, or he waits for the last minute to complete it and runs out of time.

School success requires many skill sets, and the good news is, executive function skills can be taught and strengthened. More on that in a minute.

Why doesn’t that math whiz just turn in his homework?

Some students develop executive function skills more quickly or strongly than others–even two kids from the same background or household can exhibit executive function differently. There is likely a combination of inherent and environmental factors that affect how these skills develop.

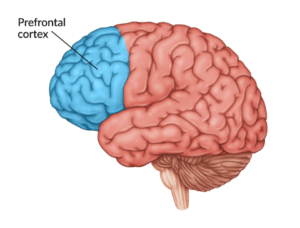

Executive function skills live in our brain’s prefrontal cortex, which doesn’t finish developing until around age 25. When discussing adolescent students, we have to remember that it is normal for skills like impulse control and delayed gratification to be somewhat underdeveloped.

Executive function skills live in our brain’s prefrontal cortex, which doesn’t finish developing until around age 25. When discussing adolescent students, we have to remember that it is normal for skills like impulse control and delayed gratification to be somewhat underdeveloped.

Childhood trauma can also impact the development of the prefrontal cortex, causing additional delays or difficulties. However, experiencing trauma is never a “done deal” or “undoable” from a brain development perspective. People can always grow and develop skills with support and practice. Our brains are incredibly moldable, and when students are not building some skills because they have urgent problems to solve (e.g. safety), they are still strengthening other capacities, such as resilience, survival, or caring for others.

Children and adolescents develop essential executive function skills in non-academic contexts as well, such as managing a household, caring for a sibling, or navigating social situations. Different skills and capacities develop differently in different life circumstances; these skills don’t always translate perfectly to the white-normative American classroom, which can be linear and unforgiving. One student’s experiences may lead them to shine in the classroom, while another’s make schoolwork difficult but will help them succeed in life. We need both.

How can I help students develop executive functioning skills?

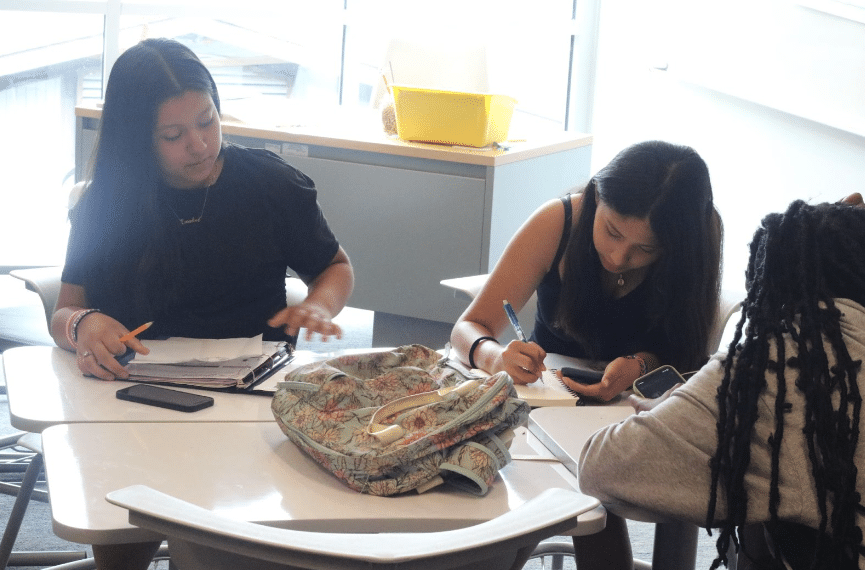

When a Student U student is struggling with executive function, they can receive individualized support from staff who are trained to guide them through these challenges and build systems for future success. Supportive strategies include

- Provide language, like “You’re not bad at school, but you need to figure out an organization system to help you complete your tasks. Right now, you don’t have structures in place to get your homework done.” Name specific skills like organization or time management that students can focus on.

- Choose a small skill to practice, like using one folder each week for all the work they need to turn in, or emptying the entire backpack every evening to avoid missing any papers. Smaller, practical strategies can help students see the outputs of organization systems so they are motivated to maintain them.

- Be the driving force in self-monitoring by encouraging students to ask specific questions like, “Does this feel like it’s helping? What can we change?”

- Remember that students want to be successful, and they want to do what works. On the flip side, they may not take on habits or systems until they see and believe the output. But when they find something that works, the habit is likely to stick. Always offer the narrative: “You can build new habits.”

Student U’s Academic Coaches lean into building executive function skills with students. Rather than trying to solve every problem for their students, Academic Coaches focus on where they can actually move the needle, such as checking and tracking grades, pulling out and organizing all the work for the week, and stopping for an Advocacy Moment–“Do we need to ask anyone for help or resources?” –then helping students communicate with their teachers.

Most classroom teachers are doing an incredible job at facilitating the executive function skills required for students to be successful, with supports like rubrics, calendars, and agendas. So much of teaching goes beyond content into making students’ tasks doable. Here are a few ways that teachers can support students as they develop executive function skills:

- Offer consistency in routines and procedures–and the simpler the better.

- Teach skills, routines, and expectations explicitly, rather than assuming students will pick up on them

- Provide simple and clear graphic organizers and rubrics

- Communicate clear end goals and the steps to get there

- Carve out regular pockets of time to maintain the systems, like encouraging students to arrange their folders or update their planners for the last five minutes of class

- Be willing to flex for students who might need simpler systems–enforce what matters, but don’t require complicated systems that themselves become overwhelming

- Provide multiple ways for students to show their learning in class; don’t let complex tasks keep students from showing what they do understand

Executive Functioning Matters

Executive Functioning Matters

These skills–organizing, backwards planning, communicating–are not “hacks” to get around the “real work.” These are the life skills that students need to be successful in the workplace, in college, and in family life. Arguably, these skills matter more than the content we learn in school because they are transferable to all aspects of life and contribute to developing successful adults.

___

Donate to Student U and keep posts like this one coming.